Armando Lara-Millán, Brian Sargent & Sunmin Kim

In this paper, we offer guidelines on how historical sociologists should engage with archives. Rather than focusing on the epistemological value of archival evidence—e.g. how we can generalize from a limited number of historical cases—we highlight the pragmatic aspects of doing historical sociology in archives: how do historical sociologists approach the material within archives? What sorts of materials should they look for while attempting to generate a theory? We argue that historical sociologists can benefit from thinking like an ethnographer. By specifying ethnographic dispositions, we lay out what it means to think like an ethnographer in archives.

Thinking Like an Ethnographer

When a historical sociologist goes into an archive, she may feel overwhelmed, for multiple reasons. First, it is difficult for the researcher to know which documents are relevant to the study. As soon as she gets into a relevant archive and opens up a storage box, she will discover that there is no folder labeled with her specific topic of interest. The challenge of identification can be overwhelming, especially for those who embark on their first archival project. Second, many individual documents simultaneously feel as if they contain one small part of the key to the puzzle and are also so trivial that they might not be worth attention. Each document may push the researcher in a small way, but collectively they can add up to something greater than their parts. Even after passing the hurdle of identification, a historical sociologist faces the challenge of weighting: what is important and what is not? Third, when faced with a large body of documents containing various ideas, behaviors, and value statements, separating what actors openly profess from what they truly believe is difficult. Actors can be duplicitous while attempting to persuade an audience in the course of making a decision. As Paul Willis (1981) demonstrated in his classic ethnography of working class youth in Britain, “penetrating” the minds of historical actors is always a difficult feat, even after correctly identifying and weighting all the relevant materials. Identifying the shortest path out of this maze becomes a key goal for the researcher. Researchers often move through these false starts and dead ends before finally reaching an effective and parsimonious theoretical explanation of complex historical phenomena.

These detours, we argue, are not just failed attempts at discovering the “right” kind of evidence, but valuable opportunities through which we can gain insights into the historical actors and processes that we aim to study. Just like an archival researcher, historical actors often experience confusion when faced with a challenge of making crucial decisions. There are too many things for them to consider, and they know too little about the possible implications of their actions. What we perceive as a historical outcome often emerges from such processes of confusion and mistakes, as a consolidation of nervous, haphazard decisions by historical actors.

Just like an ethnographer attempting to immerse themselves into a new social setting, a historical sociologist in an archive should adopt the attitude of a (purported) naive observer, pay attention to the social contexts of historical actors, and follow them along in their journey as they move through historical events. Rather than projecting an abstract explanation from a top-down perspective, a historical sociologist should first attempt to immerse herself in the situation of the historical actors, pursuing the position of “fly on the wall” eavesdropping on people in the archives.

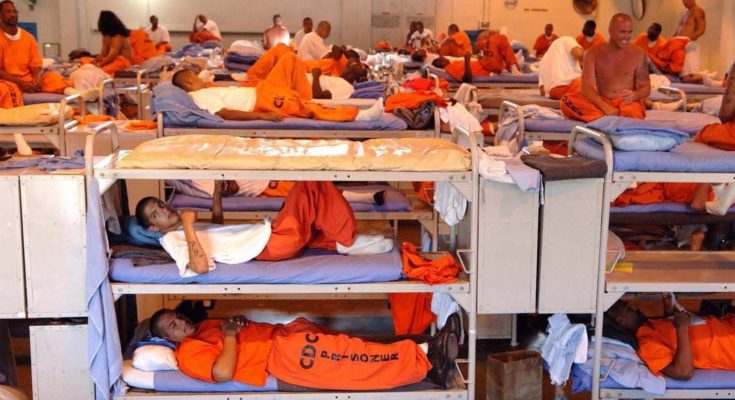

Although sociology has been late to the conversation, the methodological and theoretical discussions on archives have been going on for decades (Foucault 1982; Ginzburg 1989; Koselleck 2002; Stoler 2010; Agamben 2009), and the exchange between history and ethnography (Stoler 2008; see also Biernacki 2012; Hunter 2013) has produced a novel understanding of the relationship between archival evidence and theory construction. Drawing inspirations from these precedents, we discuss how a historical sociologist can actually think like an ethnographer in an archive. In our manuscript, we also discuss how this approach led us to rethink our respective cases in our book projects—i.e. jail overcrowding in the L.A. county in the 1990s, the federal reserve and housing desegregation in the 1980s, and the immigration restriction in the 1920s—by forcing us to consider new evidence and theory. In this feature, however, we focus on explaining the analytical leverages and pragmatic guidelines emanating from ethnographic dispositions.

Ethnographic Dispositions

Naiveté

It can be all too easy to approach the archives with a sense of knowing what comes next, due to our temporal relation to those represented in the archival materials. Simply put, by virtue of living in the present, we already know who won the key historical struggles and who survived to tell the tale. Because our interest lies not just in discovering historical facts but in constructing theories out of historical events, we tend to start with a set of research questions based on an observed outcome. The traditional approaches have often relied on comparison of carefully selected cases, designed to isolate key variables of interest. Before going into an archive, we are told, we should be able to clearly articulate our research question and hypothesis, in order to effectively obtain the answer we want. This is one way of approaching the archive, but not the only way.

We call for those venturing into the archives to approach the materials with a disposition similar to ethnographers. When an ethnographer embarks on fieldwork, she often assumes the position of a naive, untrained observer. Indeed it is often the case that an ethnographer knows little about the setting, at least not as well as the people whom she is trying to study. This naiveté is not just being inexperienced and ignorant, but a particular epistemological stance an ethnographer takes to maximize analytical leverage in the given setting. An archival researcher should attempt to approach the archive with as few presuppositions as possible, and remain open about what the story could be, what the outcome might mean, or what actors intend when they talk. Just like an ethnographer seeing the quotidian in new ways, an archival researcher should assume the position of a novice observer, leveraging her naiveté to uncover the hidden structure under the mundane.

Through naiveté we can develop a better appreciation for contingency in historical processes. As Ermakoff (2015) argued, “positive contingency”—defined as a moment when individual agency gain maximum leverage in a causal process—remains underappreciated when we look at a historical process from a deterministic perspective. By maintaining a naive stance, however, we are freed from our preconceived notions and better equipped to capture the key moments and decisions.

Observing Actions in Context

Ethnographers are typically advised to prioritize their own eyes over their assumptions about people and setting—in other words, they are encouraged to forget about who the actors are and instead collect data on how they act in their respective social settings. We tend to assume that a certain type of people (e.g. colonial administrators) act in a certain way (e.g. denigrate indigenous culture), but often times this assumption is dependent on the situation (e.g. identifying more with indigenous rulers to boast their standing in homeland; see Steinmetz 2007). As Howard Becker (1998: 45) puts it, “people do whatever they have to or whatever seems good to them at the time, and that since situations change, there is no reason to expect that they act in consistent ways.”

This theoretical perspective has implications in archives as well. When historical sociologists read documents, the focus should not only be on “what” happened, but also on “how” something happened—events and actions should be understood in their context, in their relationship to things around them. When ethnographer urge people to tell “how” something happened, it is an invitation for stories with more informative detail, accounts that include not only reasoning for whatever was done, but also the actions of others that contributed to the outcome. When going into a field site, Becker (1998: 60) “wanted to know all the circumstances of an event, everything that was going on around it, everyone who was involved,” Because he “wanted to know the sequence of things, how one thing led to another, how this didn’t happen until that happened.”

With this stance, we can understand how historical actors learn from their mistakes and change through a particular historical process. Just as researchers learn from dead ends and false starts in archives, historical actors also learn through blunders, and their dispositions and actions evolve as they engage in historical processes. By focusing on “how,” we develop a more dynamic appreciation of how actors and situations come together to produce historical outcomes.

Incrementalism

Ethnographers typically stay within a field site for an extended period of time, following along as events unfold. In the process, they pay attention to the specific manner in which events unfold rather than starting with the outcome and working backwards. Because events of interest are by definition rare, ethnographers often try to spend as much time in the field site as possible, immersed in the mundane everyday routine of the setting, waiting for that spark of eventfulness. Being there and seeing it first hand, as they say, is an ideal of ethnographic immersion, although it is easier said than done. After all, things happen fast and one cannot be present in the field site every day, every hour.

The ideal of immersion has a better chance in archives. Luckily for an archival researcher, the time in the archives progresses rather slowly. Different, but limited accounts of historical events are frozen in the format of documents, waiting to be discovered. It is as if there is not just one but a multitude of flies on the wall, reporting to historical sociologists their own accounts of how things unfolded. By going through these multitude of accounts, a historical sociologist obtains not just a birds-eye view but a Rashomon-like perspective into the historical process.

In pursuing incrementalism, we can gain comparative leverage to exclude alternative explanations. It is tempting to divide archival evidences into two camps, ones that mattered in producing outcomes and ones that led to dead-ends. In reading incrementally and sequentially, a historical sociologist is better able to pay attention to these diverging paths: what propelled historical actors to go down a particular path that was not successful? What does that tell us about the path that was eventually successful? By doing this we can see which alternative routes were actually feasible to the actors in their particular contexts and rule out explanations that made no sense to actors embedded in those contexts.

Deep Dive into Archives

With ethnographic dispositions, the troubles we encounter in the archives as researchers become an asset rather than burden. That is, much like ethnographers, we try to walk the path along with historical actors, tracing the process through which they learned, as we are learning from archival documents ourselves. We do understand that time and funding are limited for our historical sociologists, and that a historical sociologist cannot stay forever immersed in the historical setting. In order to make a new contribution to knowledge, however, one cannot avoid the exercise of getting lost and finding her way back again. We hope the ethnographic dispositions presented here help future researchers finding their way in archives.

References

Agamben, Gorgio. 2009. The Signature of All Things: On Method. The MIT Press.

Becker, Howard. 1998. Tricks of the Trade: How to Think about Your Research While You’re Doing it. University Of Chicago Press.

Biernacki, Richard. 2012. Reinventing Evidence in Social Inquiry: Decoding Facts and Variables. Palgrave Macmillan.

Ermakoff, Ivan. 2015. “The Structure of Contingency” American Journal of Sociology 121(1): 64-125.

Foucault, Michel. 1982. The Archaeology of Knowledge. Vintage.

Ginzburg, Carlo. 1989. Clues, Myths, and the Historical Method. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Hunter, Marcus. 2013. Black Citymakers: How the Philadelphia Negro Changed Urban America. Oxford University Press.

Koselleck, Reinhart. 2002. The Practice of Conceptual History: Timing History, Spacing Concepts. Stanford University Press.

Steinmetz, George. 2007. The Devil’s Handwriting: Precoloniality and the German Colonial State in Qingdao, Samoa, and Southwest Africa. University of Chicago Press.

Stoler, Ann. 2010. Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense. Princeton University Press.

Willis, Paul.1981. Learning to Labor: How Working Class Kids Get Working Class Jobs. Columbia University Press.

* This essay is from Trajectories (Newsletter of the ASA) Vol 30 (No2-3), Winter/Spring 2019. Photo is from http://www.cdcr.ca.gov/News/images/overcrowding/CSP-Los-Angeles.jpg